Alvin Brooks, Congressman Emanuel Cleaver, Kay Davis, Harrison Neal, Phyllis A. Washington, Everlyn Williams, Marjorie Williams share their experiences and insights as students, faculty, and community leaders on the effects of geographical and socio-economic boundaries on school desegregation.

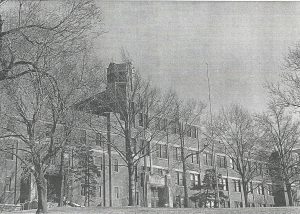

Lincoln High School

Marcelene Cooley, Lincoln High School, 1952-1956

Let me take you on a historical journey of Lincoln High and R. T. Coles Schools dating back to 1863 up to the present.

The story of the schools’ achievements in excellence is not only a vital part of the history of our community and Kansas City as a whole, but it also offers insight about the struggles and determination for success despite the socioeconomic disparities.

The 16th President of the United States of America, Abraham Lincoln ended the Civil War and abolished slavery with his signing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. However, the Proclamation provided little or no opportunity for slaves to become educated at that time. Two years later in 1865, concerned citizens of Kansas City, Missouri organized an ungraded school.

The first elementary school to educate the black children of the newly freed slaves began in a church at 10th & McGee. This school was called Lincoln Elementary School in commemoration of the great emancipator, Abraham Lincoln. As students progressed, other grades were added. Lincoln Elementary School survived several locations and in 1896 a high school department was organized.

In 1905, Lincoln High School relocated to 19th & Tracy. There was a need for vocational training in Dressmaking, Tailoring, Institutional Cooking, Automotive Mechanics, Carpentry, Masonry, Cosmetology, Printing, and Painting, and in 1915, a vocational curriculum was added to the academic program. The building at 19th & Tracy was renamed R. T. Coles Vocational/Junior High after Mr. Richard T. Coles, a teacher and principal. Mr. Coles was credited with being the first principal to introduce manual training subjects in the elementary schools. He served as principal for forty four years.

In 1936, a new Lincoln High School was built at its present location (2100 Woodland), affectionately known as “The Castle on the Hill”. It should be noted here, that all students of color in the Greater Kansas City, Missouri area were required to attend R. T. Coles upon completion of elementary school (grades K-7). After completing the 8th grade, students had the option of remaining at Coles to earn a high school diploma and a trade certificate or students could go to Lincoln to concentrate on a full academic program.

When Lincoln opened at its new location, it also took a decidedly more academic turn which included the addition of a fully accredited Lincoln Junior College on the campus, staffed largely by the regular faculty of the high school. It provided African American high school graduates an opportunity to complete a two year college program toward advancing their career. All of these achievements were accomplished within a community boundary limited to east of Campbell to Prospect and Independence Avenue to 27th Street, to include Leeds and Round Top, and east of Van Brunt.

Over the years, several grade schools existed to accommodate the black community such as Attucks, Bruce, Douglas, Dunbar, Foster, Garrison, Penn, Wendell Phillips, Sumner, Wheatley, and Yates. Students also come from Independence, Liberty, and Parkville, Missouri. Few families had cars then, so the majority of students had to walk distances to get to school or ride the bus or streetcar. It did not bother us because that was the “norm” (rain, sleet or snow). There was no such thing as “snow day” or school closings.

Rarely, if ever, did children play “hooky” because we had Truant Officers who traveled the neighborhood regularly. If a child was seen on the street during a school day, you might get stopped and questioned or picked up for truancy.

Students at Lincoln and R. T. Coles received quality instruction in both academics and vocational areas under the tutelage of teachers like Isaiah Banks, Gertrude Bardwell, J. K. Russell, Robert Simmons, Robert Wheeler, Dr. Jeremiah Cameron, Mr. Herriford, Mr. Jeffries, Mr. Pryor, and Mr. Ponder, to name a few.

The Lincoln provided students many extracurricular activities. Fraternities (Del Magnas, Redeals) and Sororities (RHO, Del Sprites, Americana Co-Eds, Akapals) which were sponsored by teachers and selected members based on academic grades. We had majorettes who accompanied the band at every game. Pep assemblies always preceded game day whereby we would sing our school song and have cheer rallies to promote school spirit. Social activities were provided at the YMCA.

Never was there a fear of fights or other disruptions. RESPECT was the rule of the day. In sports, the schools were proud of its basketball, football, and track teams. Because segregation extended beyond the classroom and into the sports arena, the school’s athletes were forced to travel in and out of state in order to compete with other students of color.

Of course, a fierce rivalry existed between Coles and the other two segregated schools in the area, Lincoln and Sumner High in Kansas City, Kansas, the only high schools for blacks on either side of the river then.

Around the time of the Brown v. Board of Education, Topeka, Kansas decision on May 17, 1954, students of Sumner High School, a segregated black school in Kansas City, Kansas, accomplished something not only unexpected, but also improbable, considering the prevailing conditions of discrimination, the sub-standard school funding, and the lower socioeconomic background of the black population that Sumner served. The accomplishment was this: Sumner dominated all Metropolitan Kansas City high schools (then more than 75 percent white) in awards for science presentations in the newly initiated National Science Fair Program.

Sumner would dominate top science prizes for much of the 1950’s. Later, Lincoln High School dominated science awards in the Kansas City, Missouri school district. Science Fair awards were not bestowed lightly. Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas City, Kansas were proud of their schools. They joined the new “International Science Fair” movement in 1952, backed by the mayor, academic and business leaders, and the public, receiving national and international recognition.

Following the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the U. S. Supreme Court ruled: “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and desegregation became effective. Little changed immediately in the Kansas City, Missouri School District. Manual Vocational High School, previously white-only, immediately desegrated and R. T. Coles closed at the end of the 1954 school year. Students officially transferred to Manual Vocational High School.

The building at 19th & Tracy that bore the names of both beloved schools, Lincoln High and R. T. Coles, were eventually torn down. Lincoln Junior College also closed in 1954. Students could request a transfer to Kansas City Junior College at 39th & Locust, but it was not automatic. Otherwise, all schools operated on the same racial basis as before.

Gradually, over the next decade, the District experienced desegregation. Resegregation of most of the schools east of Troost resulted after the exodus of many white families from the city to the suburbs.

In the mid 1970’s, Lincoln High School underwent another profound transformation. It became Lincoln Academy for Accelerated Study in 1978, Kansas City’s first magnet school. The student body and faculty experienced desegration—a condition that continues to this day. In 1986, it was later changed to its present name, Lincoln College Preparatory Academy. Lincoln has successfully survived under the outstanding principalship of educators like, Mr. H. O. Cook, Mr. George Ellison, Dr. Earl Thomas, Mr. Charles West, Mr. Harry Harwell, Marvin Brooks, Lawrence Wilson, Percy Caruthers, and Arnold Davenport, to name a few.

In the 1930’s and by the 1950’s, many of the teachers at Lincoln had master’s degrees, and several held PhDs. Conversely, in white high schools of the time, teachers rarely had more than a bachelor’s degree.

Noteworthy trailblazers whom we are proud to mention are representative of Lincoln and R. T. Coles alumni: Administrators Dr. Robert Wheeler – First black superintendent of KCMSD Dr. Girard T. Bryant – Dean of Lincoln Junior College Sports Maurice “Poncho” King – Professional basketball player for KC Steers Frank White – Professional baseball player for KC Royals Entrepreneurs Ollie Gates – Owner & Operator of Gates & Sons Barbeque; Community Developer Bruce R. Watkins – First black funeral company; political leader; first black candidate to run for mayor of Kansas City Journalism Lucille Bluford – Former publisher & journalist of the KC Call; nephew, Guion Bluford, the first black astronaut to space mission, “The Challenger” in 1983 Public Service Alvin Brooks – Co-founder of Ad-Hoc, Inc.; Assistant to the Mayor; KC Black Police Force Yvonne Wilson – Educator/Administrator; MO State Senator; community activist Clifford Warren – First black Chief of KC Police Robert Wedgeworth – Former Dean of Columbia Univ., NY; Prof/Exec. Director of American Library Association; author/lecturer; Presidential appointment to the National Commission on New Uses of Copyright. Harold Holliday, Sr. – First black student at UMKC; attorney and community activist Basil North – First black attorney for KCMSD; first black manager of a Kroger food chain in KC Veodist Luster – First black Chief of Fire Prevention, KCMO Fire Department Leon Jordan, Fred Curls, Sr., Bruce Watkins – Founders of Freedom Inc. political organization Kenton Keith – Former diplomat, Ambassador to Qatar; Sr. VP, Meridian International Center of Foreign Service Entertainment Gerren Keith – Producer/Director of TV Sitcom, “Good Times” – 1974; “Different Strokes” – 1978 Sonny Kenner, Oscar Wesley, Eddie Saunders, Larry Cummings, aka Luqman Hanza, professional jazz musicians – “5 Acres” – Eddie Bakey, Donald Parsons, Logan Walker.

Graduates of Lincoln have pursued and excelled in many professions as a result of the quality of education and exceptional leadership received from teachers, staff, and administrators. A few of the many accomplishments made at city, state, and national levels include teachers, administrators, superintendents, bankers, policy makers, college professors, curators, and regents, business owners, ministers, corporate board members and government officials. In a world that viewed us as “second class citizens”, we have become pioneers and trailblazers who have changed the social, economic, and political fabric of Kansas City by our unwillingness to compromise for less. “We are a thread in the historical tapestry of America—weaving a legacy for future generations; displaying inspiration for generations yet to come.”

Harrison Neal – Complete Oral History Interview

Harrison Neal, a former E.F. Swinney Elementary and Lincoln High School student who works as an administrator in KCPS, shares experiences with school desegregation in the early 1990s in Kansas City, Missouri. This interview was conducted on July 15, 2016 at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Education.

Anita Russell – Complete Oral History

This oral history interview with Anita L. Russell, a graduate of Lincoln High School in the Kansas City, Missouri Public School District and President of the Kansas City, Missouri Branch of the NAACP, was conducted at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Education on July 25, 2016.

Loyce Caruthers, Paseo High School, 1961-1965

“I’m Loyce ….I’m Joyce: No, I’m Joyce …That’s Loyce” “I’m Loyce ….I’m Joyce: No, I’m Joyce …That’s Loyce” was a constant refrain for us when our family moved from the segregated north end of the Kansas City to the center of the city in 1961, where we were the first generation, benefactors of the integration of Kansas City’s public schools.

For the first time, my identical sister and I attended a predominantly white school, Paseo High school. In 1954, our older siblings graduated from the only black high school in Kansas City, Lincoln High School. While white students had the option of attending seven high schools and three junior higher, black students attended either Lincoln High School or RT Coles Junior High.

I recall our walk to Paseo High School from our new home at 4109 Olive; we had on brown straight skirts and white blouses, no heels. Unaware that Black kids hardly ever used the front door of the school, we walked a half mile from our home to Paseo Boulevard and another half mile to 47th Paseo. The school was at the top of a long steep hill; and to reach the front entrance, we climbed over 50 steps in those brown straight skirts.

The large and imposing stone carved letters of “PASEO” were placed in the middle of the steps, built into the north and south sides of the hill. I remembered standing at the bottom of the hill and looking at this huge impressive structure and feeling a sense of doom and strangeness. We slowly climbed the steps, one by one, prolonging the inevitable contact with a dominant white culture.

The oak paneled walls and showcases of trophies represented a legacy that was foreign to me; and, for the first time in my life, I felt like a visitor in a foreign land. My segregated life was familiar and comfortable and here was a world where you could not expect to hear words of welcome and acceptance. I knew that my life would never be the same again.

We were eighth graders and our first year at Paseo meant that we would not be in the same classes. I was directed to my first classroom and the teacher motion to seat in a middle row toward the back of the classroom. I saw only white faces and missed the light-skinned black girl who was sitting in the middle of the front row. I sat next to a white boy, whom I later learned was Danny. He would occasionally smile at me, but I often turned my head — puzzled by his attempts to be my friend.

The light-skinned black girl blended in very well with the other students, but my carmel-colored skin did not provide such sanctuary. I felt my difference. She never smiled at me and when class was over she generally rushed from the classroom. I was so lonely and felt my “otherness” – a feeling that I can never overcome the meaning of skin color or my different speech pattern, so I grew silent. I never spoke. I constantly pulled tiny hairs from my arms. I would stare at the white follicles at the end of each tiny black hair. I was the black hair. I felt small and insignificant.

By the first semester of 10th grade, I was the tiny black hair on my arms —- I felt small and wrote small. I learned that “C” is for colored. All the black kids were aware of this phenomenon and we would smile and snigger from embarrassment. This was our way of coping with blatant racism. I never received feedback on my papers — at the top of most of my work was the red lettering of a “C”.

For 10th grade English, my teacher was a red haired white man. I didn’t know his real name — most of my teachers were “nameless” — except for Ms. Loveman, my 9th grade English teacher, who could ever forget her name. Was this her real name or did we give her that name? Most of the few black kids were in her class and Joyce was even in my class. Ms. Loveman felt she was helping us with our language and to get us to enunciate or as the black kids would say to talk white, she often told us to open our mouths and let the little man stand.

The red-haired white man, whom I later learned was Mr. Ray (pseudonym), assigned an essay for a project. I wrote in my usual small letters. I often wondered would anybody ever read my work; and, by then, my writing was unreadable to others, including me. As Mr. Ray handed me my paper, he said, “You can do better than this — redo this paper and write larger. I can’t read this.” I sat there in shock and disbelief — someone finally read my paper!

I started working for the red-haired teacher and then for myself. My grades changed from “C’s” to A’s and B’s. For a brief moment, I saw new possibilities for myself and “C” for colored took on a different meaning. It was much later in my career as an educator that I would learn of the power of high academic expectations. Just through his interactions, Mr. Ray helped me to engage academically; and by not accepting poor work from me, the “C’ for color became “C” for confidence in myself which transformed my educational experiences.

Years later, I was able to thank him when he contributed a half million dollars to the school of education. Did he remember this little black girl in his 10th grade English class from 1963? No, it was not important that Mr. Gersh, his real name, did not remember me. What was important was the encouragement and high academic expectations that he demonstrated in his teaching.